Traditional employment is becoming obsolete

2200

Traditional employment is becoming obsolete

The average citizen today is likely to spend the vast majority of their time in a virtual reality of some kind. Physical society and culture still exist – but most eschew them, in favour of the Godlike abilities they can experience online. It is very rare to meet a friend or colleague in person now. You are far more likely to encounter a form of artificial intelligence today, than you are a living, breathing human. Urban centres have become eerily deserted, with most people to be found in their homes* – or in digital libraries and entertainment venues – engaged in complex simulations that offer perfect recreations of the real world. To observers from earlier centuries, these virtual environments would appear truly dazzling in their speed and complexity, with an almost unimaginable level of detail, creativity and ingenuity.

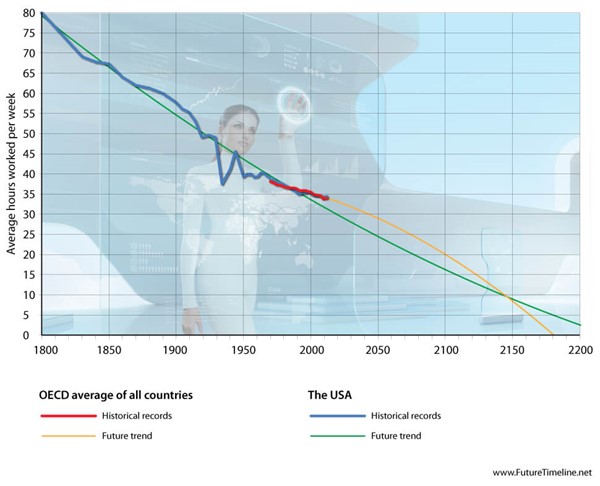

A trend which began during the Industrial Revolution has now reached its ultimate conclusion. Working hours had gradually declined over the centuries, thanks to a combination of technology, automation, improvements in working conditions and employee rights, changing labour demands and a shift in the cultural zeitgeist. By 2050, the average person in a developed country was employed for under 30 hours per week and this fell to 20 hours by 2100.* Working hours continued to fall in the 22nd century as machines – including life-like androids – took on ever more complex and sophisticated roles.

As humans began to enhance their cognitive abilities, the nature of work itself was changing. More and more people were moving from “drudge” jobs into their own personal, creative and intellectual pursuits. The line between work and play was beginning to blur. Some roles, for example, were now taking the form of extremely challenging “games”, based on subjective anomalies and problems resulting from discoveries for which AI programs were unable to offer adequate explanations. Alongside this, average spending on various household items and utilities, when measured as a percentage of disposable income, was steadily declining.*

By 2200, this trend is complete. In most countries, basic items such as food, energy and clothing are now essentially free, with little or no need for the average person to work in order to acquire them. Recent advances in replicator technology provide an abundance of resources – eliminating famine, disease and the need for war. Literally everything has been automated, digitised and made easier. Take the emergency services, for example. Hospital visits are rarely required now, as practically everything a person needs in terms of treatment is available at home, or within their own body. Police forces are dominated by robots and, in any case, physical crimes have been largely eradicated. Firefighters are no longer needed, since they are robotic too, while building regulations and nanotechnology materials can prevent most fires occurring in the first place.

This process of falling employment was, of course, by no means a smooth transition. It caused profound economic and political disruption throughout the 21st and 22nd centuries. By 2200, however, the world has fully adapted to these changes and is entering a period of artistic and cultural splendour the likes of which have never been seen before. Whether as explorers in space, or designers of entire new worlds in cyberspace, humans are free to pursue their greatest dreams and personal aspirations – unshackled from the confines of traditional economic and monetary systems.*